Full description not available

D**R

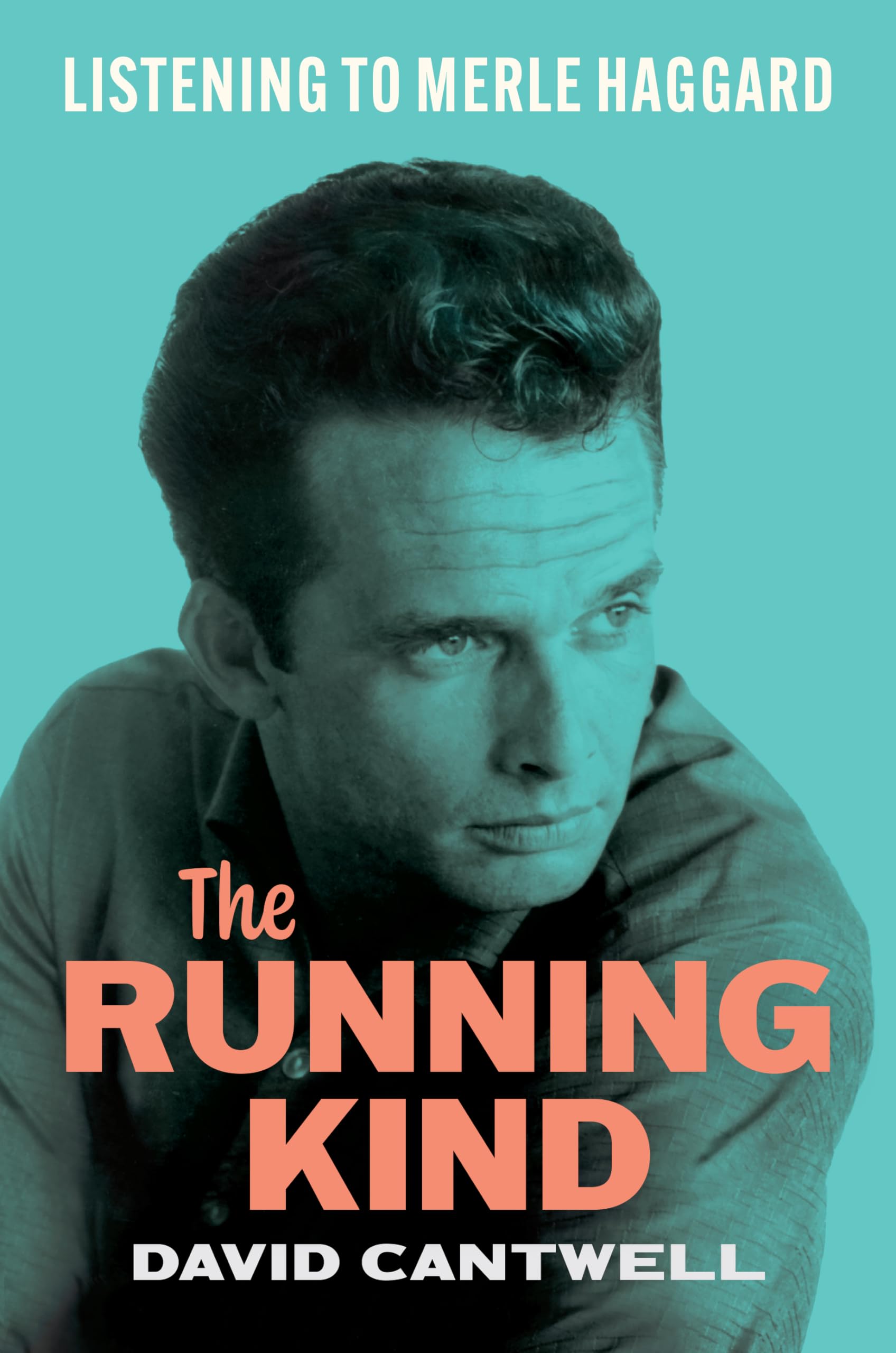

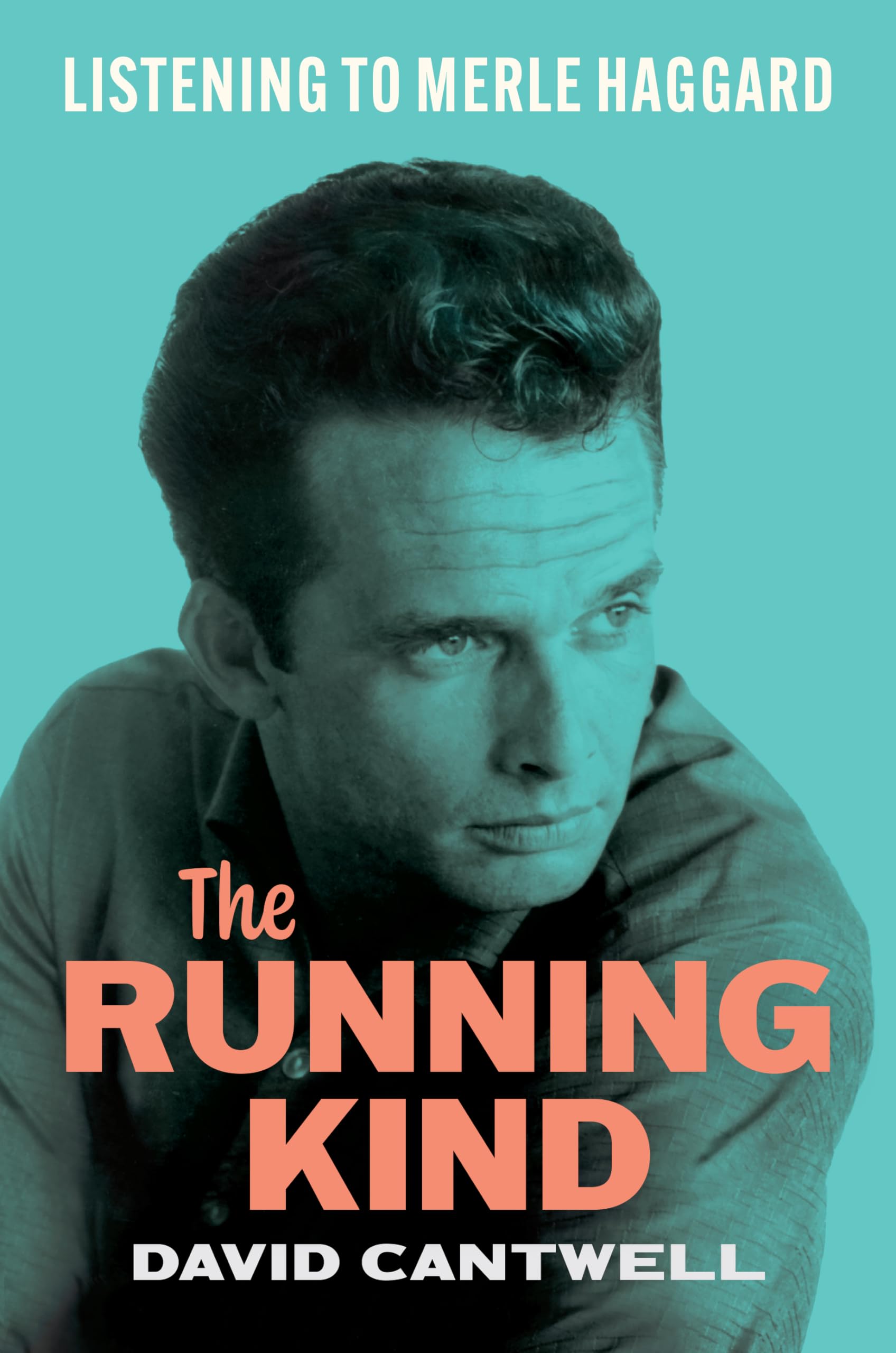

Putting Haggard to Good Use

Near the end of this new, expanded, largely rewritten version of David Cantwell’s 2013 The Running Kind, now subtitled Listening to Merle Haggard, the author declares Haggard’s legacy depends upon his music being used. Cantwell means musicians need to play it, but this book is a brilliant example of another kind of use. Cantwell pleads Haggard’s case while acknowledging his shortcomings, missteps and missed opportunities. To do this, Cantwell keeps the focus on the music itself—how a guitar part punctures, how a fiddle opens a record’s vision, how a steel guitar winks at a foolish hope, and most of all how Haggard’s voice can clip a phrase or twist a syllable to drive a point home. Cantwell’s intimate relationship with the eighty-plus albums in Haggard’s catalog continuously offer takes to give a familiar listener pause or articulates what may have seemed impossible to put into words. Even the music lovers only familiar with a few of Hag’s hits can’t help but find this book revises their sense of musical history to the good.Haggard’s role as both music history teacher and chronicler of his times demands a musical omnivore like Cantwell take it on. Having heard what sounded like his own voice in Lefty Frizzell and having heard his own story in a set of songs by Liz Anderson, Haggard embraced the connections. He recorded tributes to Jimmie Rodgers (a particularly extensive, audibly annotated two record set), Bob Wills, and even Elvis Presley, looking back to move forward like later roots rockers and hip hoppers. Cantwell centers Haggard’s story not only in country music’s evolution but as parallel and in conversation with similar developments in other genres— “Hungry Eyes” to Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Going to Come,” “Big City” to Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s “The Message” and Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska. By the time we reach the selected discography, it’s clear why Cantwell compares Haggard’s best greatest hits collection to James Brown’s undeniably important Star Time box set.Haggard’s mix of pride and shame, his yearning for place and inability to stop running all speak volumes about a country built on concepts of self-reliance, independence, and freedom that were never more than half-truths and always ephemeral. Just as Haggard’s own family moved twice to California, the Great Migration was never so simple as a one-way ticket to the promised land. Those highways run both directions, time and again, and the folks that run those roads are Haggard’s people—fleeing agricultural devastation before fleeing industrial collapse, never quite finding a solid place to land. That’s the world we live in today, uprooted, and uncertain, somewhere below somebody, and somewhere between some others.As with this working-class reality, Cantwell details how Haggard never quite fit in anywhere in the world he helped create. Though he was perhaps the outlaw to define all outlaws, he was too conflicted to fit with his outlaw peers. He sang a little too “hot” to match Willie Nelson’s approach, a little too “cool” to be another George Jones, and too “threatening and a little scary” to win over the middle-class alt rockers who embraced Johnny Cash. No doubt written with tongue firmly in cheek, “Okie from Muskogee” inescapably defines his career’s central quandary. He wasn’t the character in that song, but he couldn’t turn his back on the fans who heard themselves there. The missed opportunity of releasing the interracial love song “Irma Jackson” as a follow up shows the limits of Haggard’s willingness to confront race, but, as Cantwell writes, “he cut at least ten tracks that deal explicitly with race. Not that many to be sure, but at least 1,000 percent more than every one of his contemporaries and every one of his musical descendants.”Cantwell writes about the intersecting commonality and conflict surrounding race and class in America like few others, and that gives him a crucial perspective for appreciating Merle Haggard. When politics turn toward identity—as they regularly do in this country that enslaved one group of people for hundreds of years, all-but wiped out the indigenous, and has never stopped pitting its poor against each other—an artist like Haggard is of unique importance. As Cantwell shows, Haggard’s political perspective evolved over the years, but he never lost touch with the roots of his raising, the daily realities of the great numbers of whites who barely keep their heads above water while being labeled trash. In a country that’s never stopped fighting the Civil War facing the epochal change of a technological revolution and a rapidly shrinking and dying world, Cantwell’s emphasis on the country aesthetic, “changes, connected” (not incidentally, the aesthetic of jazz, which Haggard also uses) puts Haggard’s aesthetic to work, suggesting just how we might find our way to one another, “to stories bigger than our own,” and to a future where we no longer feel compelled to run, scared and alone.

D**U

Americana’s Misunderstood Legend

The Running Kind is a collection of essays on key periods or songs in Merle Haggard’s enormous catalog. Obviously Cantwell spends most of the book on Haggard’s time on Capitol, but his career downturn during the 80s and 90s and Haggard’s turn of the century renaissance are explored as well. Several obscure releases even kicked off a Discogs deep dive for me to locate them.Sure to ruffle a few feathers, Cantwell’s work is a fantastic exploration into the catalog of one of country music’s most misunderstood legends.

Trustpilot

1 week ago

1 week ago